A chance encounter one evening led to this in-depth interview with Heather Alwen, wife of Chairman Roger, recalling the build-up to Charlton’s eventual return to The Valley after seven year’s in exile. First published in Blizzard, the football quarterly.

“Heather, red or white?” called out Charlton’s Keith Peacock, looking straight at me as he turned from the bar in the plush Millennium Lounge at The Valley. The occasion was not a matchday but a Q&A session, part of the 2017-18 season-long celebrations of the 25th anniversary of the founding of Charlton Athletic Community Trust and the return of football to the stadium in South East London.

As dapper now as he was assured on the wing, Keith Peacock is my Charlton thread of continuity, the link between the muddy pitches of the 1970s and the bespoke-carpeted, club-crested hospitality lounges of today. I was too young to witness his history-making first ever football league substitute appearance. Yet when I first started attending The Valley as a kid he still regularly trotted out in trademark fashion: juggling the ball from foot to foot into the penalty box in front of the Covered End then blasting it into the back of the net. But how on earth would he know my name?

An assertive female voice answered over my shoulder, “Red, please, Keith.” I looked around to see an elegant, smartly-dressed woman, a couple of decades older than me. Another Heather? We’re usually thin on the ground in London, let alone in a male-dominated football environment. It dawned on me that the wife of erstwhile chairman, Roger Alwen, one of the night’s speakers, was indeed called Heather. Thanks to an oblivious Keith Peacock, we got chatting.

Charlton remain the only English football club to leave their traditional ground and then return many years later. Roger Alwen’s beaming image is seared on my mind from the frequently replayed video of 5 December 1992, the day Charlton came home for the match against Portsmouth. With a mop of unruly hair, square wireframed glasses, club tie and double-breasted blazer, he pushes open the sparkling red metal gates and confidently leads the Addick faithful back onto the hallowed, yet still steaming, tarmac of The Valley.

Where was Heather at that point, I wondered? Subsumed amid the throng of over-excited, exuberant fans, perhaps? “I was arranging flowers in the Portakabin,” she reveals. At the time of the return – and for some while after – the offices, boardroom and even the dressing room of this phoenix stadium were humble temporary blocks on the car park behind the equally temporary West Stand. This was The Valley, but not quite as we used to know it.

Heather and Roger both grew up in Sevenoaks, Kent, and met as teenagers. Heather was just 20 when they married, Roger three years older. Roger’s father had died when he was very young. His mother didn’t drive so she took him on the bus that ran from Sevenoaks to home games at The Valley: “It was the one thing she felt she could do with him that his father probably would have done…so that’s how his love of Charlton grew.”

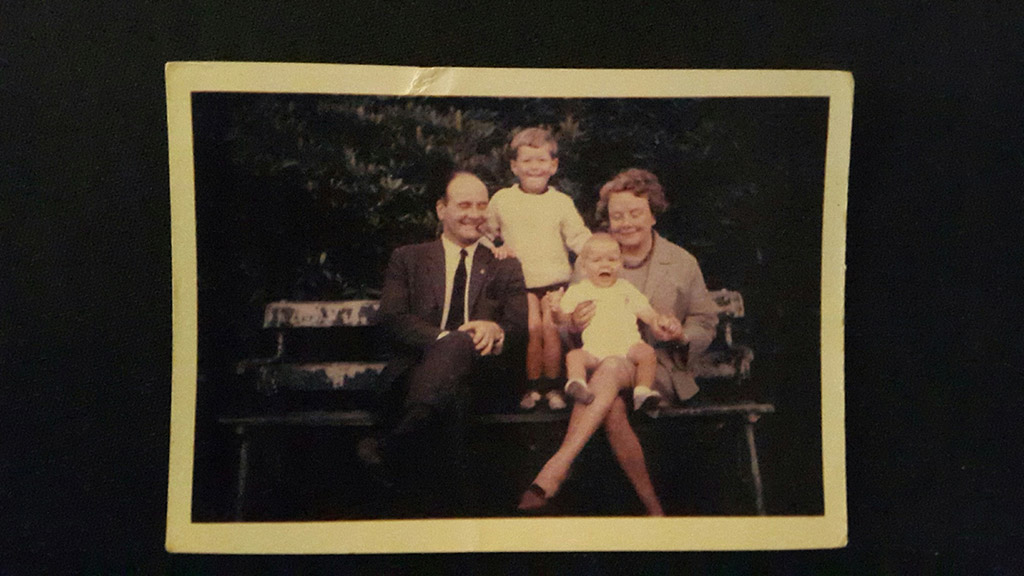

The Alwens had three children and Heather’s previous passion for horse-riding was replaced by outings to football: “The children simply loved it and I did too. Charlton in those days was very much family-oriented. It was always fun, lovely people around you who’d entertain the children. We stood on the East Terrace. The children would be passed down to the front so they could see. It was relaxing, you never felt threatened.” This would have been in the early to mid-70s. I, too, was becoming Addickted at around this time and Heather’s memories chime with my own. I stood with my dad further back on that vast bank, where space was not at a premium. The Valley boasted a capacity of 66,000 yet was rarely graced by more than 5-10,000 turning up to witness second- or third-tier contests.

The financial consequences of underachievement, overspending and tax debts caught up with the club. In February 1984, it very nearly disappeared altogether, saved in dramatic fashion not on the pitch but at the High Court. The new owner was Sunley Holdings, ominously a building company. In September 1985 Charlton played their last match at The Valley – supposedly. Abruptly displaced to share a stadium with Crystal Palace, eight miles away around London’s South Circular, fans found the physical journey in the capital’s Saturday-afternoon traffic tortuous enough. The emotional wrench, however, was greater than many could bear.

Around this time Roger Alwen, a wealthy city man, was gradually becoming more involved with the business side of the club, thanks to his friendship with Derek Ufton, a former Charlton player turned director. Alwen joined the board in summer 1987, seriously concerned about what the future might – or indeed might not – hold. “Selhurst virtually crippled the club,” affirms Heather. “The fans stayed away. They didn’t like it, they had no home. That was Roger’s main worry – not what division they were in or going to be in – but surviving. They weren’t going to.”

As a first step to re-establishing Charlton in its heartland, Roger and his fellow director Mike Norris bought a training ground in New Eltham, still used to this day. “We built a home there,” explains Heather. “It wasn’t in great shape but it got better and better. At Selhurst there was nothing.”

Heather made her mark. “My other love is gardening. The players used to laugh at me in the flower beds. The wind used to whistle right across. I planted – to my shame – leylandii as they grow so fast, to provide a screen. It was all hand-planted – daffodils too to make it a welcoming place. We also got a pool table and I made a cloth with a big Charlton logo on it – something to identify with.”

Mrs Alwen’s support of her husband extended to taking a maternal interest in the players’ welfare. At the time nutrition had a much more basic meaning than today’s carefully-balanced scientific-led dietary approach. “We put in a kitchen and canteen. Particularly the young ones from very poor backgrounds were not getting fed properly at all. We’d get them weighed and measured, give them meat and two veg every day. Then we had different ethnic groups – curries on the menu etc. It was a learning curve but I think we succeeded.” On the evening when I first met Heather, former Charlton striker Carl Leaburn was present. I witnessed first-hand the genuine affection between the two of them as they reminisced that a once spindly and under-nourished Leaburn was Alwen’s inspiration for setting up such facilities. I smiled wryly as now he is a mountain of a man.

With the training ground up and running, Alwen and Norris set about acquiring the freehold of The Valley once more. “That was not easy,” recounts Heather. “John Sunley, of Sunley the builders, was still under the impression that one day he’d get planning permission. It was the only reason he’d bought it, the reason to move to Selhurst Park. He let The Valley fall into disrepair… it was absolutely disgusting, revolting in every sense. He felt the worse it got, the more clout he’d have with the council to build houses as it would ‘improve’ the site.” With this candid explanation, the chairman’s wife confirms the worst fears of fans at the time.

A wave of optimism swept over the Addicks as news broke in early 1989 that The Valley freehold was back in friendly arms. But, after years of abject neglect, it was a site to make the eyes sore. “Roger had this idea. He wanted to get the fans back. So we had an open day at The Valley on a Sunday morning – everyone was invited to come and clear the site. It was mega, extraordinary. People turned up in droves, there was a big bonfire in the middle. If fans wanted to take old seats with them, they were welcome. What they didn’t know of course was that the next day the bulldozers and JCBs turned up and actually cleared the site. The fact they’d pulled up a buddleia wasn’t going to make a lot of difference but it was a tremendous atmosphere, a lovely idea.” Despite the insider knowledge that the day was essentially a PR exercise, Heather found herself in the thick of it: “I was on the East Terrace pulling up nettles and things and there was a darling old lady next to me with a dustpan and brush. And as I pulled things up, she came along and swept up after me. It was so sweet. She said, ‘I live in a flat, dear, and I don’t have any gardening things so I thought if I brought my dustpan, at least I could clean up after everyone.’ I mean wow – fantastic. So that was really the start of going back.”

But it was by no means the finish. The saga leading up to the fairy-tale return is one of wheeling and dealing, differing agendas, finances stretched to breaking point, planning battles and – most famously of all – the fans forming a political party. Rick Everitt’s book Battle for The Valley provides the definitive story from an activist fan’s perspective. At times the author is critical of the naivety of Roger Alwen and his fellow directors.

While staunchly defending her husband’s good intentions, Heather answers honestly when I enquire if they had any previous experience in such planning matters: “Absolutely not. Not on this scale. Putting a conservatory onto a house or something but nothing like this.” She goes on to describe the frustration of the public planning meetings. “You are not allowed to say anything – you sit and you listen. A couple of councillors couldn’t even speak any English. One of them always called us the Athletic – didn’t even know we were Charlton Athletic.” Heather goes on to recount how she attempted to engage one of the female councillors empathetically after a late-night finish to a fractious meeting: “I said, ‘You really have to go through awful times – why did you ever become a councillor?’ And she said, ‘My dear, the sandwiches are very good.’” Such a patronising reply clearly still rankles in the memory despite the lapse of time.

Property owners in the vicinity of The Valley lobbied the council hard, fearing the fortnightly invasion of hooligans and louts – such was the image of supporters of the beautiful game in this era. For Charlton fans, such nimbyism was astonishing, given that the football ground had loomed large in the backyard of South East London since the excavation by volunteers of the old chalk and sand quarry in 1919.

Like a team that’s 2-0 down at the break, the Addicks regrouped to think again and a new tactic emerged. The Valley Party burst onto the scene. Resolute door-knocking and leafletting supported by an emotive billboard advertising campaign resulted in 14,838 single-issue votes, almost 10% of those cast, in the Greenwich local elections of May 1990. While no seats were won, the usually stable Labour vote was sufficiently rocked to unseat the fans’ nemesis, the Chair of the Planning Committee, Simon Oelman. “That was an amazing evening,” recalls Heather, “I’m looking at the picture here, the election results. What the Valley Party did was just fabulous. Without them we wouldn’t have got here.” The council had to concede. The previously blocked permission was granted.

Charlton were heading home. Or were they? For the Alwens what happened next turned out to be “a very rocky road, a dreadful road, financially a real nightmare – people don’t realise – huge pressure for both of us. Roger had put just about everything into it. Then we had a huge setback and Roger was left holding the proverbial baby.” Normally quite assured, Heather’s voice trembles slightly as she recounts the difficulties. “Roger had always said to Mike Norris that whatever money you put into Charlton it must not be borrowed money – this is a bottomless bucket – you’ve got to be able to afford to lose. Unfortunately, Mike was a property man and he gambled on the fact that the property market was very buoyant then all at once it collapsed. A nightmare. Mike, bless his heart, had to pull out. Roger suddenly found himself owning Charlton with the banker.”

To compound matters, Charlton had given notice to end their increasingly disharmonious tenancy at Selhurst Park. Without the funds to complete the redevelopment of The Valley, the club was once again on the brink. A detour north of the Thames to Upton Park meant the club could fulfil its fixtures while Roger scrimped and scraped enough money together, including from player sales and fan appeals, to secure the long-awaited return on 5 December 1992. “Everyone rallied round,” explains Heather. “People wrote in and offered help. The ground staff were superb. Our youngest son never wanted to see a pot of red paint again.” To add to the sense of celebration, the date coincided with the Alwens’ wedding anniversary.

After the return, Heather took on a day-to-day role at the club. “Roger asked if I would come and help out in the office. He didn’t have to pay me – free labour! I sat on reception, I helped with Valley Gold [fundraising scheme], I was literally doing the secretarial work.” Heather is a capable and intelligent woman, yet at the time she willingly accepted her place: “In those days it was very, very much a man’s world. I was quite unusual in that I was so involved. The players accepted me. I would never voice an opinion on anything other than what they would assume a woman would know about – gardening, cooking, arranging flowers, and I was happy to stick to that.”

Surely there must have been an element of frustration? “Oh lord, yes, I could run the club! Absolutely, don’t know why they had a manager!” While this reply is tongue-in-cheek, the former chairman’s wife is certainly pleased that the world of football is gradually changing. and highlights Karren Brady as a role model. “I met her in the very early days at Birmingham – just had her first child – clamped to her hip in boardroom and I thought wow. She was amazing even then. Quite forthright – said things I wouldn’t have dared. She has done brilliantly. She is tough – she got a lot of flak for speaking out. She has always stuck to her guns and I do admire her.”

Now in her early seventies, Heather Alwen would not profess to being at the vanguard of women’s liberation in football, though she certainly saw the funny side of the old traditions. “We had some hilarious times,” she recalls, describing away matches where the directors of opposing teams didn’t know what to make of her and fellow director’s spouse, Judy Ufton, let alone where to put them. “We were never allowed in any board room – we were usually ushered into some little cubbyhole under the stairs. One time at Stoke there was a TV in the corner on a shelf so I said to one of the director’s wives – they were always very sweet and charming – ‘Does the television work?’ and she said, ‘Of course, dear, is there something you want to watch?’ And I was thinking, ‘Well, maybe the results!’”

A significant legacy of Mrs Alwen’s contribution to Charlton can be found in the south-east corner of the home stadium. “We had a slight problem. When people died, the family wanted their ashes scattered at The Valley. But that’s not very practical in the goalmouth as bone ash – bone meal – burns grass.” So Heather created a memorial garden in the corner between two stands. “I put some ground cover plants there. The chaplain would come and do a service then the family would go back to one of the bars for a drink.” The garden continues to bloom today and act as a place of remembrance, one of the few in the country sited overlooking the pitch.

With new investment coming into the club, Roger was replaced as chairman of Charlton Athletic by Richard Murray in mid-season 1994-95. “Roger felt he had done everything he’d set out to do,” confirms Heather. “Whoever holds the purse strings really should be in charge. I went back to my career with the British Red Cross. It was difficult to take a backward step having been so involved but we were fine; you knew it was right; it couldn’t go on forever.”

Aside from beating Portsmouth 1-0 on the Valley return, Heather’s other abiding memory is no surprise. “Wembley 98 – it was a surreal time – I’ve never been quite so tense at any football match, not even the first one back at The Valley.” Having drawn 4-4 after extra time, Charlton beat Sunderland 7-6 on penalties to secure a place in the Premiership. “When he [Michael Gray of Sunderland] missed that penalty – wow – an extraordinary feeling – I don’t know how to describe it. We had a massive party after with the entire family and friends but everyone oddly enough was quite quiet – it hadn’t sunk in. The next day we realised, reading it in the press and things. Great times.”

I ask if Heather still follows Charlton. “Of course. When you’re involved you have a very different relationship with the club. Now we’re back to being fans.” She regularly attends at home but admits to no longer travelling away: being just a random supporter among what can sometimes be a lairy crowd is too much of a contrast from the days of being hosted – even if only as a segregated director’s wife. “I was spoilt for years – that sounds a bit awful, doesn’t it?”

I reflect that I still keenly sing and shout in the thick of it at away games. Not only such behaviour separates me from this other Heather. We are a generation apart and outlook and a class or two apart in upbringing and wealth. Mrs Alwen defers to any football club patron who pays the bills whereas I rail insubordinately against absentee and uninterested ownership. I am no fan of Karren Brady. I suspect that we hold differing opinions on many other matters beyond football. Regardless, I feel a bond that goes beyond our first name and penchant for red wine. Charlton Athletic made it back home, thanks to the famous contributions of the Valley Party and Roger Alwen. Myself and Heather Alwen, along with countless others, experienced the extremes of despair and jubilation of that tale from the shadows, simply faces in the football crowd. Such acute emotions and common memories nevertheless create a powerful link. And help explain why we both remain Addickted to this day.