The achievements of Jerry Kerr are such that he deserves to be lauded as one of the pioneering Scottish managers alongside the likes of Jock Stein and Bill Shankly. But for decades he was not even welcome at Dundee United, the club he helped shape. A poignant story based on interviews with the family.

First published in Nutmeg Issue Three, March 2017, and featured in Scotland and Sunday.

“As a manager, he never swore, never lost his temper, was never rude to anyone. He was respected as a gentleman and there aren’t many managers of the modern game you can say that about.” Rhona Haston, an elegant lady in her seventies, talks with warmth and passion about her late father, Jerry Kerr. I am meeting Rhona and her son, Ross, to hear more about this intriguing man, who clearly meant the world to them.

Rhona hands me several black and white photographs. Despite my keen interest in football, I am embarrassed to admit that I know next-to-nothing about the balding, well-dressed figure, sometimes sporting a trilby, nearly always puffing on a pipe, usually managing an affable smile. Yet this is a man whose achievements in transforming his club should be lauded in the Scottish Hall of Fame alongside Jock Stein’s Celtic triumphs and Bill Shankly’s galvanising of Liverpool.

Jerry Kerr’s record as manager of Dundee United from 1959 to 1971 was exemplary. As a condition of accepting the job, he insisted the team turned full-time. He dragged them up from a lowly place in the second division to become an established top-flight side, for the first time placing them on a competitive footing with Dundee. He managed the club’s money as carefully as his own, grateful for the cash delivered by the novel commercial concept of Taypools. Seeking ideas and value abroad, he imported a wave of Scandinavian players to complement the young Scots whom he would talent-spot himself on the amateur pitches. Kerr personally supervised the building of Scotland’s first cantilever stand at Tannadice. He was the first Dundee United manager to beat the rivals from across the road, the first to take the club into Europe and the first to secure victory home and away against Barcelona. Even the tangerine kit and the fans’ nickname of the Arabs originated under his watch.

So why is Jerry’s name not immediately associated with anything and everything we recognise of Dundee United today? Rhona’s voice cracks with sadness tinged with self-confessed bitterness, emotions unhealed by time: “It’s not a nice feeling. It was unpleasant and got more unpleasant. My father was airbrushed out.”

Rhona describes the point in 1971 when her forward-thinking father knew the time was approaching for him to relinquish team duties: “Dad was coming up for 60. It was the start of the tracksuit managers. He was not a tracksuit manager but he realised that was what teams were doing.” Jerry recommended bringing in a young coach from Dundee, Jim McLean, to be manager of the team while he would become General Manager. Jerry was not a man of ego, but he was a man of ideas, principles and determination, who was used to leading from the front. Within a year, the situation was untenable. He was pushed out of the club he had built, without fanfare or even thanks.

Indeed, it was rival club Dundee who took him under their wing. Jerry had a role with the SFA as President of the Second Elevens, a position that depended on being affiliated to a club. He was due to attend a meeting at SFA Headquarters. “But by then he was away from United, they’d kept it very quiet,” Rhona explains. “The manager of Dundee, Dave White, phoned and said, ‘Well, we’re going down to Glasgow tomorrow, Jerry, and there’s space in the car for you to come.’” It was a sign of the respect in which he was held elsewhere.

No-one can deny that McLean built further success upon the stability created during Kerr’s twelve-year managerial tenure. But as he did so he trampled and compacted Kerr’s foundations so far below the Tannadice surface that there was barely a whisper of his predecessor left. Jerry was no longer welcome at United and he knew it. In all his remaining years, until he passed away in 1999, he never set foot there again.

Only when Eddie Thompson took control could Jerry’s name once more be associated properly with the Tangerines. The new owner hosted Rhona, her brother Gillon and the wider Kerr family at a pre-season match in 2003 versus Everton. At the request of the Federation of Dundee United Supporters’ Clubs, the main stand was to be named in Jerry Kerr’s honour, more than three decades after his unheralded departure. The supporters had earlier mooted the idea to Jim McLean, who reportedly dismissed it: “We don’t name stands after dead people.” Nowadays the wraparound cantilever structure hosts away fans, which perhaps explains why the name Jerry Kerr is somewhat familiar. Reflecting on the belated recognition, Rhona says, “Dad would be pleased now. I don’t know about mum. For a long time, mother and I were quite bitter, but dad never was.”

Like many of his more famous contemporaries, Jerry came from humble beginnings. Born in 1912, he grew up in Armadale, West Lothian. Rhona reflects, “They were quite poor. Dad appreciated everything. There was no side to him, people were just people.” His family nevertheless harboured ambitions to improve their working-class lot. Jerry’s Mum was keen that her son should get himself a proper job. She arranged an interview for him at the local Atlas Steel Works, “for an office job, with a collar and tie,” Rhona recounts. But the young man had an independent streak – he skipped the interview, instead finding work as a joiner at a firm down the road, “because he wanted to work with wood.” He stayed with the company for thirty years, progressing to a managerial role.

Kerr also enjoyed a lengthy playing career as a full back, predominantly as a part-timer or amateur. From the age of fifteen he turned out for Armadale Thistle, and at seventeen he was picked up by Rangers. “He told me he had to turn up there in a bowler hat and spats, but he was probably having me on!” Rhona laughs. He played just once for the Ibrox club, enough to receive a silver goblet in celebration of Rangers’ centenary in 1973. He went on to play for Alloa and St Bernard’s before joining Dundee United in 1939 and captaining them to the War Cup Final.

You can’t believe all you read on the internet, and that is particularly true of Jerry, even down to his name. He was raised by his family simply as John Kerr – no sign of Jerald or Jasper or any such exotica on his birth certificate. Daughter Rhona is not even sure where the name Jerry came from, only knowing that it had stuck by the time of his marriage. “All his family knew him as John, but my mother’s family called him Jerry.” I surmise that actors often have stage names and many footballers have pitch names. ‘John’ might have been all too common, among both team-mates and opposition. Perhaps one of the other lads mashed together his initial and a chunk of his surname and added a friendly -y? We’ll probably never know.

Jerry’s playing days had other long-term consequences. Ross affectionately remembers venturing into the little room in the house where his grandfather watched TV from his big leather armchair, describing it as “the wonderful world of his smoky den.” Here pipe-puffing Jerry would recount stories of a bygone era. “He told me how he had to sit in the bath in his tough new leather boots to get them to mould to his feet. He also said he went bald from heading those big heavy footballs!”

Jerry’s heart was in football and he naturally graduated into management, first of all at Peebles Rovers then at Berwick Rangers. Competing with Dundee was already in his sights: his lowly team dumped them out of the Scottish Cup in 1954. Rhona, a teenager at the time, has vivid memories of this unusual squad. With a trainee minister and professor of maths among their playing ranks, they were known as the Wise Men of Berwick, accompanied wherever they went by “celebrity” fan, Mimosa Meg, who sold posies outside the ground, home and away. Meg even ventured to the big city as the Cup run came to a halt at their Glasgow namesake.

Jerry moved on to become manager at Alloa Athletic. Rhona assisted her father on his scouting missions. “I was at college and wanted to learn to drive. The only way was to go with him – up to the playing fields at Saughton and all over. I’d take my books and do my work in the car while he’d walk the fields, watching matches to see who he could see. I was with him outside when he saw John White.” Rhona is understandably proud that her father was the first manager to sign the frail but tricky inside forward, whom the Rangers chief scout had apparently watched thirteen times. White went on to make a name for himself at Tottenham Hotspur, gaining one too as admiring fans dubbed him “The Ghost” because of his ability to appear from nowhere.

In 1959, Jerry Kerr finally achieved a full-time role in football, successfully applying for the manager’s job at second division Dundee United. Forget glitz or glamour. He brought his wife and mother to Tannadice to show off his new office. Rhona envisages the scene as her grandmother exclaims, “Oh, Jerry, look at that table, it’s got woodworm!” The new man in charge, fully aware of the challenges facing him, calmly replies, “Mother, the whole thing is falling down. A table with woodworm is the least of my worries.” Bit by bit, Jerry took control and fashioned the club along his own lines. In his first season, the gamble of turning full-time immediately paid off and the team achieved promotion.

The only way his small club could compete, Kerr recognised, was through innovating. And that meant looking beyond Scottish borders. Attending the famous 7-3 Real Madrid v Eintracht Frankfurt European Cup Final at Hampden in 1960 proved inspirational. Rhona reminisces, “Dad always said that was the finest game he ever watched – he didn’t even mention beating Barcelona!” He struck up a friendship with the manager of the German team, Paul Oswald. Rhona describes her parents’ visit to beautiful training camps in the Black Forest. Her father was keen to learn about the German training techniques, extending to fitness and diet. “It was the kind of thing he did – Dad always wanted to be a step ahead of the game, but it was difficult when you didn’t have money.” With post-war austerity and rationing still all too recent a reality in Scotland, her mother was taken aback by how wonderful Frankfurt was. “Germany had been on its knees. Yet they were being served platters of beautiful roast beef – they thought they would be to share but it was one each. It made mum wonder who had won the war.”

As for most of his generation, the war contributed profoundly to making Jerry the man he was. He missed out on the first four years of his young son’s life while away in the army. It also shaped him as a football manager. Asked by Dundee Courier reporter, Ron Thompson, how he remained so unflappable and calm while watching his team from the dugout, Kerr replied, “Well, I landed in Normandy on D Day. That was fear. I was in a hole, a shell hole, and I thought if I get out of this, nothing will ever make me frightened again. It’s only football.”

Little was insurmountable for the new Dundee United manager. Ron Yeats was his captain but was called away for national service. Rhona describes how her father jumped on a train and went down to the army base in England to get them to agree to release the colossal centre half to play whenever needed. “I remember meeting Yeats with dad in the Buchanan Hotel in Glasgow. Ron was a big lad, a rough diamond. He looked awful with his army haircut. He complained, ‘Boss, my feet are killing me from all that square-bashing.’ Dad replied, ‘You’re lucky to be here. Now get out there and play!’”

Kerr called upon his experience in the trade to supervise the building of the new main stand, recognising the need to invest in better facilities. Rhona remembers the firm went on strike just before the season started. “Dad took his jacket off, there in his shirtsleeves, digging at something. Someone said, ‘Oh come on now Jerry, you know better than to break the strike’ and he said, ‘I don’t care, I need this stand to get the spectators in.’”

Such a dogged attitude and determination to succeed lie at the source of the “Arabs” nickname. In the harsh winter of 62/63, the Tannadice pitch was so deeply frozen it resembled a skating rink. Desperate to prevent a fifth postponement of the cup tie versus Albion Rovers, Kerr ordered industrial tar burners. These did indeed thaw the ice but also stripped the grass. Coarse sand was spread on top and the referee gave the go-ahead. With the surface resembling the Sahara, the home side, playing in white, completed a 3-0 win, supposedly “taking to the sand like arabs”. Fans embraced the concept and now many Dundee United supporters’ clubs incorporate the name and occasionally don the costume.

Money was always a concern and Jerry effectively acted as day-to-day treasurer. Rhona recounts how he carried the money in his back pocket when they went on tour in the summer, several times to Africa and then to the United States. “He would count every penny.” This was well before the days of package holidays: international travel was an adventurous journey, even for footballers. Jerry instigated the tours as a way of ensuring income to pay the players over the summer. But he also knew the value, especially when visiting poorer countries. “They were on the bus in Nigeria. Dad got all the Nigerian money off the players, saying, ‘It’s no good to you people, but a lot of use to this man.’ He gave it to the driver who got out and hugged dad round the legs. It meant a lot.” Jerry struggled with the contrast between wealth and poverty. Rhona remembered him feeling very uncomfortable in Mexico, staying in a plush hotel while beggars were lying on the street outside.

With his team struggling at the start of the 64/65 season, the manager was desperate to uncover talent more cost-effectively and less competitively than in central Scotland. A local scout in Broughty Ferry helped Jerry explore the Scandinavian market through a Danish contact. The manager signed up five players as professionals: Finn Døssing and Mogens Berg from Denmark, Swedes Örjan Persson and Lennart Wing and Norwegian Finn Seemann. By this time, Rhona was married and Jerry had no hesitation in accepting help from his son-in-law, Robin. “When dad brought Finn Døssing over, he arrived at Turnhouse airport and got the papers signed. Robin took them and drove all the way to Glasgow. When he got there, the SFA was closed so he put them through the letterbox. He phoned my father from a call box – no mobiles then, of course – and left word that he had dropped the papers in. Dad said, ‘Just as well as he’s on the field!’ He never liked to do things wrong, but he would find roundabout ways of doing things right!” Rhona also describes her mother’s efforts to make the young men welcome in Scotland: “Mother made smorgasbord for the players – she always backed dad up, tried to help him.”

With the Sixties in full swing, Kerr’s Viking invaders contributed significantly to the Terrors’ success, helping stave off a potentially disastrous relegation. The following season they finished fifth to qualify for Europe. Prolific goal scorer Døssing, former firefighter and left half Wing, and future Rangers winger Persson all went on to feature in the United Hall of Fame. They blended well with home-grown talent, such as young Ian Mitchell and Dennis Gillespie, whom Kerr brought with him from Alloa.

In their first ever European tie Dundee United were drawn to play the holders of the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, Barcelona, with the away leg first in October1966. “People didn’t have enough money to go,” explains Rhona. “Mr Barton, then the owner of the Taycreggan Hotel in Broughty Ferry, hired a mini bus to take seven or eight supporters. This was a team that no-one had heard of, some of the boys had never left Scotland. They ran out to thousands of home fans and this handful. At the end, there was stunned silence apart from this wee group of diehards.” Kerr’s special blend of Scots and Scandinavians, having taken the lead in the 13th minute and doubled it from the penalty spot, hung on for a remarkable 2-1 triumph.

The return leg, now over 50 years ago, still boasts Tannadice’s record attendance. 28,000 wrapped up warm against biting cold gales to witness the white-clad Terrors secure a 2-0 win. The aggregate score might have been even more embarrassing for the Catalans: marauding United had two further goals ruled out for offside. Such a feat demanded better than the luck of the next round draw: Italian giants Juventus. Despite another packed house and home victory, the club’s first European jaunt came to a close.

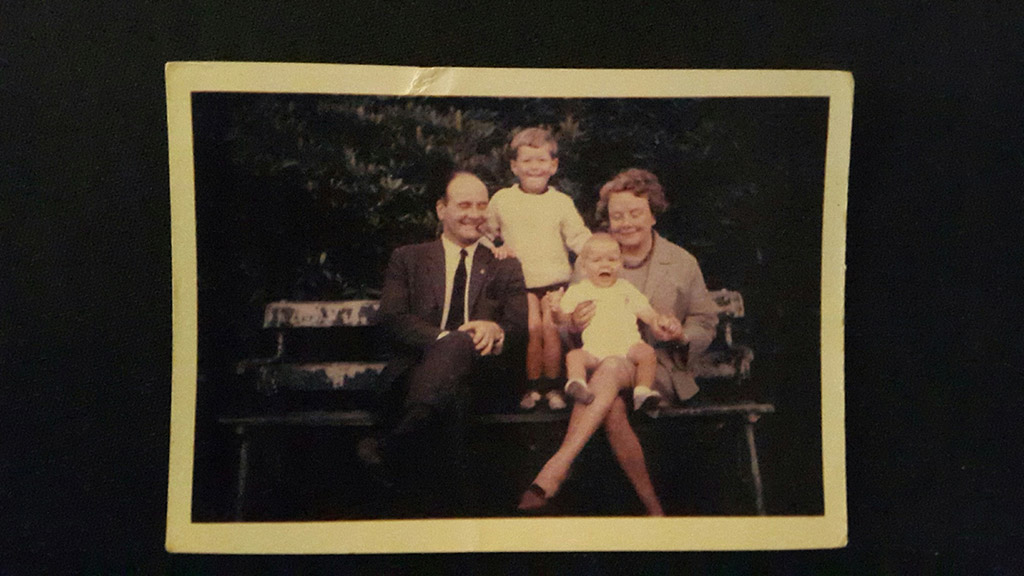

Towards the end of the same season, Rhona describes taking her two small boys to see their grandfather at Parkhead. “We arrived after half-time – we were living in Bathgate while dad was in Dundee so it was a chance for him to see the children. Ross was running up and down the corridor. There was a door half open and Ross ran in. Then dad appeared, ‘Oh come away out of there son, that’s Jock Stein’s room and he’ll be in a bad enough mood as it is, we’ve beaten them home and away!’” Celtic only lost two league matches that season, both against Kerr’s men. Just three weeks later, the Lions won the European Cup in Lisbon.

On the back of their new-found fame, United were invited to the States in the summer of 1967. Several British teams, adopted by local cities, went over to play in the tournament. Rhona takes up the story: “Dad took Dundee United to Dallas. It was purely and simply to earn money. He loved it. They played as Dallas Tornadoes. Lamar Hunt was the famous local millionaire, big on the tennis circuits, and he was trying to sponsor European soccer in America. He and dad became great friends – he gave dad a Stetson – thought it was funny!” The connection between the two men went further than the hat. Only after Jerry died, when going through his things, did Rhona come across a scroll making her father an honorary citizen of the Texan city.

In an interview with the Celtic View in 1970, reprinted in 2000, Kerr shared some of the secrets of his success, describing the essential qualities of a good football manager: “He has to be able to build up confidence in his players – make a chap believe that he’s maybe a better player than he really is. You’ve got to be a morale-booster and a psychologist.” Perhaps reflecting on the challenges he faces nowadays as a company director, Ross highlights the ongoing relevance of such words in any walk of life. “I learnt so much from Jerry. I thought he was both inspirational, and entrepreneurial, while behaving like a gentleman at all times.”

Jerry was the kind of person who made a big impression. He was a well-known figure around Dundee. “I remember as a child, wherever we went, people would want to stop and shake his hand,” recalls Ross. Women would come up and give him St Christopher’s to keep him safe on his travels and he could get away with parking on a yellow line for ten minutes, with the blessing of the warden.

Yet the most striking and visible legacy of the Kerr era at Dundee United was not initially down to the man at all. Until the late Sixties, United played in white, with black as the occasional away kit. Jerry’s wife, Barbara, had a strong opinion on this. Rhona describes the conversation: “Mother said, ‘It looks so much more rugged on a cold winter’s day when they are wearing all black. Don’t have them wearing white, it looks puny. I don’t like it.’ He said, ‘I can’t have them wearing black, it’s the second strip.’ ‘Well,’ she said, ‘change the colours.’ He said, ‘I can’t do that, we’re registered.’ She said, ‘You can do anything, Jerry, if you put your mind to it.’” Colour televisions were all the rage and orange was a very fashionable colour. “People think it was because they wore it as Dallas Tornadoes, but really it was mum’s idea,” insists Rhona, going on to describe how a rather embarrassed Doug Smith, then United’s captain, had to model a sample of the bright new strip for the directors’ meeting. They decided to go for it. “I remember much later dad meeting a man in a sports shop in Kirkcaldy and he said, ‘Jerry, I don’t know how you did it but you made me a fortune – all the kids want the tangerine strip.’”

Every now and again Rhona’s eyes glisten with tears of pride because she is the daughter of a man as fine as Jerry Kerr. She has a gift for bringing to life the words of her father and scenes from the past. So many of these tales have been dammed up in a close family circle for decades, untold stories from the heart of Scottish football. They deserve to come flooding out.

The admirable character who did so much to shape the future at Tannadice, the gentleman who turned the Terrors tangerine, is finally being properly remembered and celebrated at his club. The family are welcomed back and their memorabilia is on display in the recently-opened museum. Managerial names such as Shankly, Stein, Wallace and Ferguson trip effortlessly off the tongue of Scottish football enthusiasts. It is about time that the name of Kerr, baptised John, known as Jerry, joined them. I for one will be nominating him – about a decade later than he deserves – for the 2017 Scottish Hall of Fame.